Rev John Henslow of Hitcham

Despite having worked in the area for a number of years, I had never been inside All Saints Church in Hitcham. So I was looking forward to this, my first time.

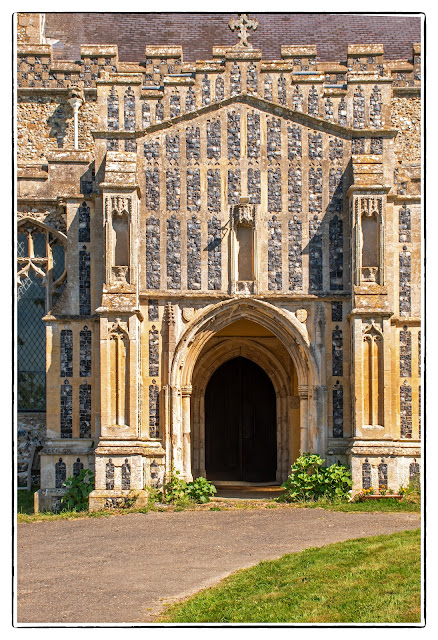

My first observation was that the church has a massive tower, built around the 15C, with a rather good looking South side entrance.

The south porch entrance.

And so into a lovely light and airy interior. Unusually, the church has not a single piece of stained glass. The nave is seperated from the two outer aisles by the simple octagonal pillars of the five bay arcades that probably date from the 14C.

Hitcham Church features a significant "Adoration of the Magi" painting, a copy of a work by Rubens, which is located in the south aisle. This painting, a reverse copy of the original at King's College Chapel in Cambridge, is a notable feature of the church. The painting is said to have come from the palace of the Bishop of Bath & Wells and was described as a copy of an old master.

The fine double hammerbeam roof

The font was installed in 1878 but moved to its presnt position in the 1930`s

Memorial to Rev John Stevens Henslow. For me, the main interest in this Church and Parish

John Stevens Henslow was born in Maidstone, Kent, in 1796, the eldest of eleven children. His father was a solicitor and his grandfather, Sir John Henslow, had been Master of Chatham Dockyard and Chief Surveyor of the Royal Navy. His was a family of amateur naturalists and the children were encouraged to add to the household collection of insects, fossils and anything of natural interest. As he had a flair for collecting and classifying, young Henslow, whilst still a schoolboy, was invited to assist staff at the British Museum in cataloguing its growing Natural History collections.

Thus began Henslow’s lifelong interest in science and scientific education.

He went up to Cambridge in 1814 and as there were no Natural Science courses then, he took his degree in Mathematics. It was only during his postgraduate studies that he was able to follow his scientific interests and in 1822, at the age of 26, was given the Chair of Mineralogy. Five years later, in 1827, he was appointed Regius Professor of Botany.

In addition to his required lectures, Henslow organised field trips for his students, but his most popular custom was to hold weekly soirées at his home in Cambridge to which anyone who had a scientific interest was invited to come and join in discussion in an informal and social atmosphere. It was during these gatherings that Henslow came to know and to recognise the outstanding ability of a diffident young undergraduate named Darwin. In 1831, Henslow was asked to recommend a suitable naturalist to join HMS Beagle for its scientific survey of South American waters, and he persuaded Charles Darwin to accept the post. It was during the five year voyage of the Beagle that Darwin began to compile his vast collection of notes which he subsequently condensed into “The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.”

The Henslow-Darwin connection did not end at Cambridge, they remained close friends, and in 1860, the year before his death, Henslow chaired the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Oxford, where “Origin of Species” was debated and where Thomas Huxley, in his celebrated defence of Darwin, declared that he would sooner be descended from an ape than a bishop. Henslow’s own comments were unrecorded, but there is little doubt that he regarded Darwinism in particular, and science in general, as enlarging our view of God, and giving us a greater respect for the rest of creation.

There is also little doubt that Henslow himself would have liked to have accompanied the Beagle. Perhaps that is why the invitation came to him, but by 1831, he was not only a married man but a clergyman too; he had been ordained Priest of the Church of England in 1824.

John Henslow came to Hitcham in 1837, a village described at the time as being “a populous, remote and woefully neglected parish, where the inhabitants, with regard to food and clothing and the means of observing the decencies of life, were far below the average scale of the peasant class in England.”

He immediately set about the task of improving the quality of life of his parishioners. But not from the pulpit. It is recorded that Henslow’s first congregation in Hitcham Church was insufficient to fill one pew, and although a first-class lecturer, he was regarded as an indifferent preacher. Perhaps he felt uncomfortable in speaking six feet above contradiction. With Victorian confidence and practicality he saw that education and the application of scientific knowledge offered the best solutions to the impoverishment that he found around him.

He found the farmers of Hitcham to be hard-working but intensely conservative in their methods of husbandry. He found their workers. who made up the bulk of the population, to be underemployed and invariably the victims of poor harvests and economic downturns.

He believed passionately in scientific agriculture and persuaded local farmers to assist him in experiments on crop diseases and measured analyses of manures. On a family holiday in Felixstowe, his restless, enquiring mind caused him to examine substances found in the cliffs there, known as coprolites. He recognised that coprolites, which are the fossilised excrement of animals long extinct, contained a high percentage of phosphate of lime, which he believed would provide a highly concentrated fertiliser. He conducted experiments, published his results and lectured at Suffolk Farming Society Meetings. Two young Suffolk farmers were so impressed, that they gave up their farming work to exploit the coprolite deposits, and from these humble beginnings, the international chemical company of Fisons, once based in Ipswich, evolved. There is a small back alley in Ipswich, close to the Docks where the fertiliser was crushed and prepared, called Coprolite Street. A reminder, perhaps, of Henslow’s holiday in Felixstowe.

Throughout his ministry in Hitcham, Henslow maintained his position as Professor of Botany at Cambridge, and was also, for a time, a private tutor to Queen Victoria’s children. But his teaching was not confined to bright undergraduates or to royal offspring. Shortly after arriving at Hitcham, he founded a village school and timetabled himself for regular lessons during the school year. His lessons were naturally Botany and nature study. Henslow was no mere chalk and talk classroom teacher. His surviving teaching notes show carefully prepared lessons which involved the children in collecting specimens, dissecting them and preparing notes and drawings of their findings. A teaching method still regarded as exemplary. Henslow believed that learning and enjoyment went hand in hand.

His beliefs in the potency of education did not end with the school children. He was deeply concerned with the overall poverty of their homes and families. Their fathers, farm workers subject to the vagaries of the day labour system, worked to exhaustion at some times of the year, during ploughing and harvest, for example, and stood off with little or no pay at other times; whose only recreation was in beer which they could ill afford. Their mothers, prematurely aged through child-bearing and drudgery.

As Rector of Hitcham, Henslow was responsible for the administration of the Village Charities, which traditionally gave handouts to the poor at Christmas, much of which they were relieved of at The White Horse. He changed this by substituting coal for money (a system which still prevails in the village, although now it’s electricity tokens for pensioners), but more significantly, he used the resources and influence of the charity to provide gainful occupation and extra food throughout the year. He introduced allotments to the village. In the teeth of opposition from the farmers who feared the loss of labour when they most needed it, he badgered them into making available plots of land which their labourers could cultivate, produce their own vegetables and develop an absorbing interest in gardening. As well as providing practical advice, Henslow instituted an annual vegetable show at the Rectory where those parishioners who had responded to him could proudly show off their produce and receive prizes for “Superior Allotment Culture”.

With the coming of the railways to Suffolk, Henslow organised excursions to places where Hitcham people were unlikely to have visited before, such as Cambridge and Norwich, and, in 1851, to the Great Exhibition in London. Each trip set off from Stowmarket station and was meticulously planned so that his party could see and enjoy as much as possible in the time available.

Henslow could also be described as the father of scientific archaeology in Suffolk, in that he undertook the first excavations in the county for which plans and sections survive – these were on the Roman barrows Eastlow, Rougham 1843-4. He was also one of the founders of Ipswich Museum.

John Henslow died of an attack of bronchitis in Hitcham in 1861. He had lived a life full of achievement, only fragments of which are described in these brief notes. He has had two biographies, one written in 1862 by his brother-in-law, Leonard Jenyns and a recent one by Jean Russell-Gebbett, published by Terence Dalton of Lavenham in 1977. This is available in local libraries.

Comments